Zendaya murmurs into my left ear.

"My planet Arrakis is so beautiful when the sun is low."

I nudge back.

"My planet Arrakis is so—"

Okay, I'm hearing a lot of breath, yet the phrase and point of view remain very legible. I inhale, record a phrase into Adobe Audition, and listen:

. . .

I need to enunciate more. Another take:

. . .

Volume’s too loud. I run a mental check list: make it breathy, hit the key consonants, but keep the vowels low. I try again:

. . .

I like this. I make a note of how that take felt in my imagination and body—in a hollow at the back of my chest, as if I’m piecing together a daydream for someone behind me—and move to the next line.

Hard work fine tuning a whisper.

In everyday discussions surrounding fame, we commonly equate the concepts of star and celebrity. To be a famous person—to be widely known and remembered by others—is to be a star.

As Britney so iconically sings, “‘She’s so lucky, she’s a star.’”

But film scholar Richard Dyer, in his influential books Stars1 and Heavenly Bodies,2 offers more expansive ways of defining stars. For Dyer, stars are not just celebrities, but also “images in media texts.”3 When he uses ‘image,’ he does not mean that a star is “an exclusively visual sign, but rather a complex configuration of visual, verbal, and aural signs.”4 Put another way, a star is every bit of information that is publicly available about a given celebrity:

A film star's image is not just [their] films, but the promotion of those films and of the star through pin-ups, public appearances, studio hand-outs and so on, as well as interviews, biographies and coverage in the press of the star's doings and 'private' life. Further, a star's image is also what people say or write about [them], as critics or commentators, the way the image is used in other contexts such as advertisements, novels, pop songs, and finally the way the star can become part of the coinage of everyday speech . . . Star images are always extensive, multimedia, intertextual."5

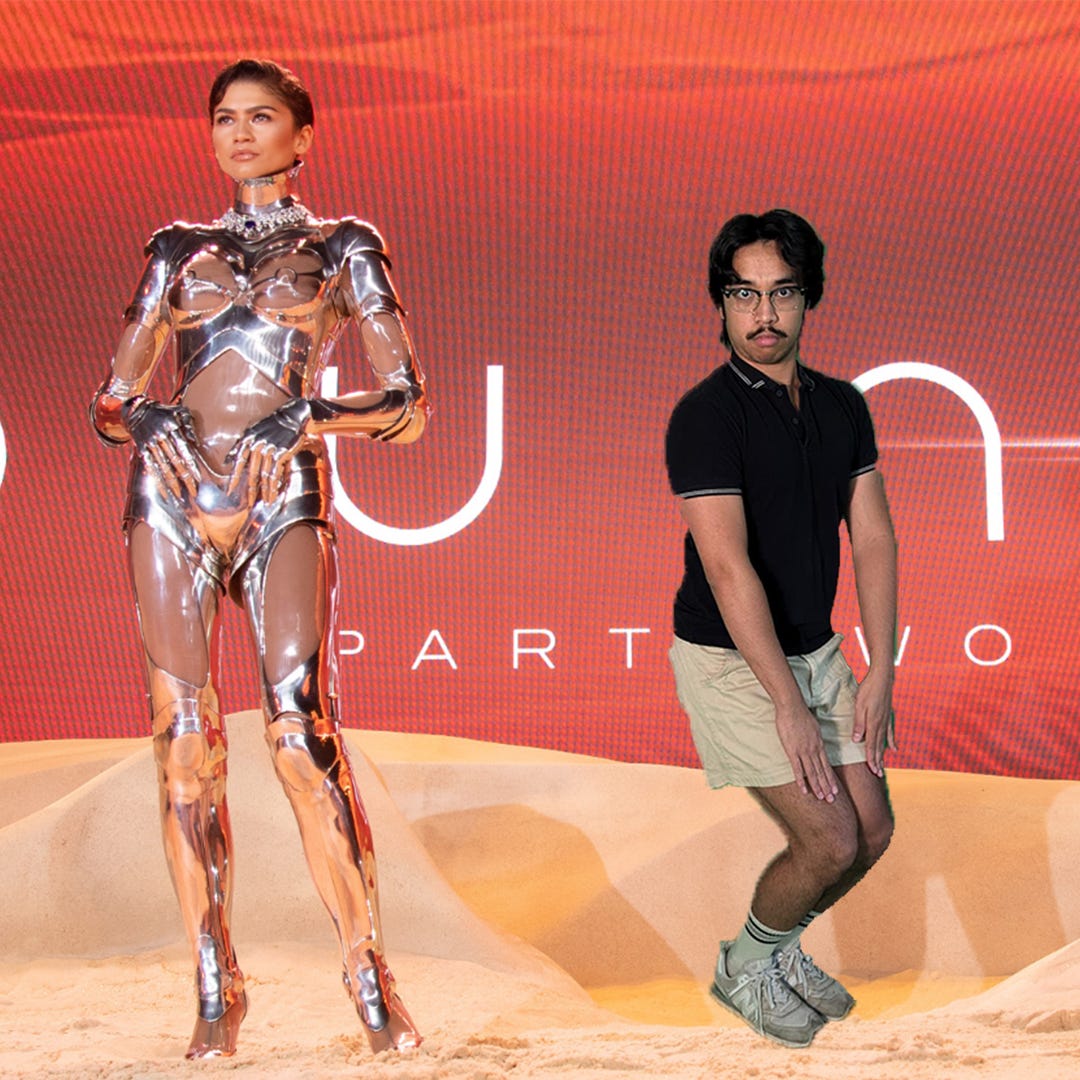

At the center of the assemblage that is a star, of course, lies a literal human. Wade beyond the glamorous pictures of 21st century A-lister Zendaya on magazine covers and red carpets, and we can find Zendaya Coleman, a fellow '96 Zillennial from the Bay Area (🤭). Thus, the common conflation of star and celebrity.

Dyer, however, complicates the idea that famous person and star are the same thing. He concedes that popular cultures can contain an “elision of star as person and star as image,” though he is most interested in investigating the latter—for when we engage with a celebrity, “we never know them directly as real people, only as they are to be found in media texts.”6 In fact, throughout Stars, he continuously makes explicit distinctions between his analysis of a celebrity (in which he uses the word ‘star’) and his analysis of the informatic assemblage swirling around a celebrity (in which he uses the term ‘star image’).7

Echoes of this discursive move—the naming of a person’s fame as separate from themselves—ripple throughout contemporary culture.

This year alone features several instances of people describing a celebrity’s fame as a star they possess. Cultural critic Scaachi Koul, in the Nickelodeon exposé docuseries, Quiet on Set, describes the star trajectory of a now infamous (and very harmful) children’s television producer: “Over the '90s, Dan's star is rising in Nickelodeon.”8 Club pop icon Charli xcx, in her tribute to the late artist SOPHIE, “So I,” sings of the latter’s lasting legacy: “Your star burns so bright.” And Vogue editor Marley Marius, in her cover story on Zendaya for last May’s edition, ends the feature with a provocative question: “Now that her star is shining more brightly than ever, how will she use its light?”9

This is a simple linguistic step, going from being a star to having a star. But I think the conceptual separation between a famous person and their fame opens up expansive theoretical space, within which we can understand the innerworkings of stardom with greater analytical clarity.

Let’s dig deeper.

Once again, to build upon Dyer, a star is the multimedia amalgamation of stuff about a famous person that exists in our collective consciousnesses: the aggregated amount of shared attention and memory dedicated to a particular person (or even place and thing!).

If stars are tethered to widely known things, then we can say that celebrities do not function as stars, but rather as anchors of stars. Star anchors, if you will: the literal humans with finite lifespans who can experience the same gamut of emotions as you and me. The physical people who eat and drink and burp and fart and live and die. As anchors, famous people act as gravitational centers for grand sums of collective consciousness that can sometimes live on for thousands of years after the anchors’ physical deaths.

Alexander the Great, as anchor, is long dead, but his star continues to shine to this day (in small part thanks to my mere act of mentioning his name).

This distinction between star and star anchor has a lot conceptual utility. For instance, it can help us better articulate a perennial tension when talking about celebrities: the fact that they are ‘just like us,’ yet also not because they live in their own bubble of fame (Dyer calls this the ‘ordinary-special dialectic’). With the language of star anchor and star, we can distinguish the ordinary parts of stardom (the anchor: the literal human, dead or alive) from the special parts (the star connected to the anchor: the tens of thousands of screaming fans in stadiums, the hundreds of millions of followers on Instagram, the billions and billions of streams on Spotify).

If we make this clarification, then we can understand that yes, anchors are like us in the sense that they are also mortal, human beings, meaning that we should generally try to extend to them the same amount of grace and patience we might extend to the mortal, human beings in our everyday lives. And yes, anchors are not like us in the sense that many of their actions operate within a place of concentration—concentrated attention, wealth, cultural sway, political power—thus placing upon anchors greater levels of scrutiny and expectation.

In any case, we must remember that when we interpret a celebrity’s statement in an interview or on social media, we are not reacting to the star anchor: the literal, actual, physical human. Instead, we are reacting to the star, the snapshot of the anchor that can extend way beyond the literal person.

This Substack, for instance, can be considered a part of my star (modest as it may shine). Let’s see if it takes on a life of its own.

Following the theoretical separation between star and star anchor brings us to the star pyramid, the broader conceptual apparatus that underlies stardom. At the base of this pyramid, we can then talk about star launchers, star audiences, star archetypes, and even stardom modes—but I’ll save these (very juicy) topics for subsequent posts. ;-P

Until then, thanks for reading!

KC

0:-) @ii

Dyer, R. (1998). Stars (2nd ed.). British Film Institute.

Dyer, R. (2004). Heavenly bodies: Film stars and society (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Stars, p. 10.

Stars, p. 34.

Heavenly Bodies, pp. 2-3.

Stars, p. 2.

Unless, of course, you are have close, personal relations with a famous person.

Dyer, himself, seemingly goes against this move in Heavenly Bodies by defining ‘star image’ as consisting of both “what we normally refer to as [their] ‘image’, made up of screen roles and obviously stage-managed public appearances, and also of images of the manufacture of that ‘image’ and of the real person who is the site or occasion of it. Each element is complex and contradictory, and the star is all of it taken together" (p. 7). I read this as further proof that defining a star has been a muddy endeavor overall, thus warranting conceptual effort for greater clarity! ;p

Robertson, M. & Schartz, E. (Directors). (2024, March 17). Rising stars, rising questions (Season 1, Episode 1) [TV series episode]. In Robertson, M., Saidman, A., Holzman, E., Carlson, N., Stonington, J., Taylor, K., & Deustch, P. (Exective Producers), Quiet on set: The dark side of kids TV. Maxine Productions; Sony Pictures Television Nonfiction; Business Insider.

Marius, M. (2024). The dreamlife of Zendaya. Vogue.